On October 15, 2008, I had an essay published in Library Journal called “Stranger Than We Know” which was my attempt to try and understand where the next 10 years would take technology and libraries. Written just after the release of the iPhone 3G, I was trying to think carefully about what the smartphone explosion was going to do to culture and technology and how that would impact the world of information gathering, sharing, and archiving.

While I didn’t get everything right, I am proud of the general direction I was able to sketch out, even if I was perhaps a bit utopian, and entirely missed the issues with misinformation and always on social networks.

Here is the article as originally written…it doesn’t appear to be available online through Library Journal any longer, so I’m self-archiving it here to ensure it’s findable online.

Stranger Than We Know

Originally published October 15, 2008 in Library Journal netConnect, Mobile Delivery pg 10.

Arthur C. Clarke once famously said that any sufficiently advanced technology was indistinguishable from magic. The technology that is now a routine part of our lives would have been nearly unfathomable just a decade ago. Moore’s Law has ensured that the two-ton mainframe computer that once took up an entire room and nearly a city block’s worth of cooling now comfortably fits in your hand and weighs only ounces. It is difficult to put the truly amazing nature of this shrinkage into perspective, but consider this: you have in your mobile phone more computing power than existed on the entire planet just 60 years ago.

These new devices are changing the way we interact with information. Their capabilities are even changing how we conceive of information and information exchange, adding significant facets such as location and social awareness to our information objects. The physicist J.B.S. Haldane once said, “[T]he Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” So while librarians are aware that the next five to ten years will bring radical changes to books, publishing, and the way we work with the public, we must remember: the future isn’t just stranger than we know-it is stranger than we can know.

Let’s see how close we can get to knowing the unknowable.

The vanishing cost of ubiquity

Several forces are combining to make mobile phones the most attractive method of accessing information across the globe. In countries with a well-developed information infrastructure, mobile phones are embedded in most people’s lives. Reuters estimates that by the end of 2007, 3.3 billion people had some form of mobile phone, and in some countries the penetration rate actually exceeds the number of people. As an example, in June 2008, the Hong Kong Office of the Telecommunications Authority estimated that there were 157 mobile phones for every 100 people living in the city. In countries without a well-developed information infrastructure, cell towers and phones are the most economical method of catching up, costing orders of magnitude less than stringing wires over the landscape. In addition, communications companies have adopted the Gillette model of sales, where the initial hardware is highly subsidized. This makes the buy-in reasonable compared with the very large up-front cost of a desktop or laptop computer, an investment difficult to justify for many in the First World, and impossible for those in the Third.

This omnipresence of cellular signals is quickly being adopted for even nonphone applications, strictly for use as a data pipe. Increasing numbers of laptops now have cellular cards as options, and even noncomputer digital devices, such as the Amazon Kindle, are beginning to show up with cellular connections. When this particular trend crosses streams with the increasing popularity of so-called UMPCs (ultra-mobile PCs) and subnotebooks such as the Asus Eee PC, we end up with incredibly small computers that are always connected to the Internet.

In addition to always-on connectivity, this new class of device is also likely to contain a multitude of features. With the ability to fashion chipsets that include more and more functions, the cost to include add-ons such as GPS (Global Positioning System) and cameras is more of an engineering compromise related to battery consumption than it is any real cost to the device in terms of size and weight.

We’re now living in a world where we have nearly omnipresent devices, most of which have the capability of being connected to a central network (the Internet), and the majority of which have very advanced positioning and media-creation capabilities. What can they do?

A place for context

There are several high-end phones these days, but the current media darling is clearly the Apple iPhone 3G. Running Apple’s OS X operating system, the iPhone 3G combines a huge, brilliant display with a multitude of connectivity options (Edge cellular data, 3G cellular data, or traditional 802.11 Wi-Fi) as well as GPS, a camera, and the power of Apple’s iTunes Store for the distribution of applications that run on the phone and extend its abilities. Taken together, these apps are a clearinghouse of clever ideas that combine the technology of the phone with the real world to provide a window onto where we may be heading.

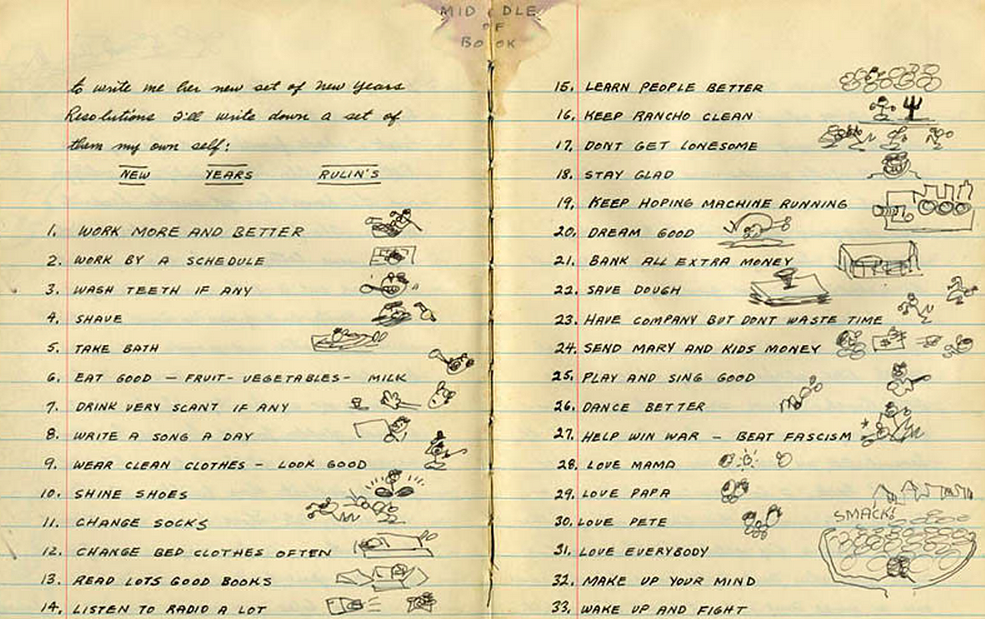

The Omni Group produces a task-list manager called OmniFocus, which is essentially a very fancy to-do list. But it’s an intelligent to-do list and organizes your tasks via what it calls “Context.” For example, the Home context is used for those tasks I can only do at home, Work for those at work, Phone for those that require calling someone, etc. You can, thanks to the GPS in the iPhone, geolocate any of these Contexts with their position on the planet, so that the app knows where Home, say, is. Now that all the pieces are there, the application is smart-when you call up your to-do list, it only shows you those things you can do where you are standing and not the things you can’t. When you change locations, your to-do list reacts appropriately.

This type of location-based information is part of the next step in information use. Imagine geocoding reminders in this way, so that your device could inform you the next time you were within a mile of the grocery store that you needed to get detergent. Or, using this type of information interaction with a social network, having your device remind you the next time you were with a certain friend that you wanted to ask him for his salsa recipe. When information is given context (in library parlance, metadata), the information becomes more useful. When you can easily structure your information and make it scriptable and logical, responding to if-then conditionals, your information begins to work for you.

Getting local-and personal

Other examples of truly amazing mobile technology are just being created. My favorite current model is the Enkin project (enkin.net ), a combination of graphic manipulation and geolocation that adds metadata to the real world. Imagine standing in downtown New York, wondering which buildings you are looking at across the street; you pull up your phone and aim the camera in that direction. The camera captures a few photos and sends them to a database of geotagged images that compares yours against the broader set until it hits a match. The phone then overlays the image on your screen with information about the live scene in front of you, telling you the name of the building and when it was built. Extending the existing proof of concept, a natural next step would be to pull up historical photos of the area, overlay them, and let you watch the progress of time.

Examples like these exist, even if only in beta. What can we expect to see from mobile devices in the next three, five, or ten years? While Moore’s Law even today makes it possible to have cell phones that are so small as to be unusable, in the future the same law will simply allow for higher and higher computing power and storage to fit into the same form with which we’re already familiar. These devices will combine wireless standards (Wireless USB, Bluetooth, 802.11a and n) to allow for communication on multiple levels all at once. The device may be checking where you are in the world while also talking to the devices of those around you, sharing information as they go. The desktop as we think of it now will be given over to a terminal that pulls its computing interface from your mobile device, allowing you to carry your personalized computing environment with you anywhere you happen to be.

Within five years, we will see the blossoming of the 700Mhz spectrum, a newly licensed communications frequency band for wireless devices. The existing infrastructure in the United States is hampered by legacy support and historical structures, but the new data infrastructure should take advantage of all of the developments of information and communication science over the last 20 years, without the need to build in backward compatibility. This should give us the next generation of wireless data, as well as a platform for the public to use-imagine an open cellular network that was more like 802.11: it will be required to have open access components, preventing telecom companies from locking it down and allowing for localized uses similar to 802.11 hot spots.

In addition, there will be a multiplicity of services geared toward these mobile devices. Within ten years, music and video will be delivered as subscriptions, where a flat fee gets you streaming access to the entirety of the celestial jukebox and any and all video available, both TV and film. These devices will also have a new hybrid OLED/E-ink screen that displays text for ebooks in a resolution that makes it as comfortable to read as a physical book, with a multitude of titles available for rental or purchase instantaneously through an on-screen library. Popular media will be on-demand and available anywhere you happen to be, while the flowering of independent media production that is going to take place in the next five years will add thousands of options to your consumption of news, sports, and other live events.

Even more significant, these devices will act as a hub for your most personal of area networks, tracking data from a series of sensors on various parts of your body. The future of medicine is in always-on embeddable sensors that give doctors long-term quantitative data about your body: pulse, breathing, blood-oxygen concentration, glucose levels, iron levels. A full blood workup will be delivered wirelessly via RFID from your subdermal implant.

We have a current model for this in the Nike+iPod device, as well as the new Fitbit, which tracks movement, fitness, and sleep patterns, but future devices will be far more robust. This Body Area Network will extend itself and not only gather information about you and your surroundings but will enable a cloud of information sharing in a flexible but secure manner, amassing and comparing information as you move through the world so that you won’t be caught unaware of environmental hazards again. As an example, imagine walking down a street as your mobile device suggests your route to work based on the allergen counts that it picks up from other walkers.

The cloud librarians

So how do librarians interact with this level of mobile, always on, information space? The most important thing we can do is to ensure that when the technology matures, we are ready to deliver content to it. Our role as information portals will not decline-it will simply shift focus from books on shelves and computers on desks to on-time mobile delivery of both holdings and services. Reference will be community-wide and no longer limited to either location (reference desk) or to service (IM, email, etc). It will be person to person in real time. Libraries’ role as localized community archives will shift away from protecting physical items and toward being stewards of the digital data tied to those items in the coming information cloud, ensuring that our collections are connected to the services in the online world that provide the most value for our users. Our collections will be more and more digitized and available, with copyright holders allowing localized sharing founded on location-based authentication. If you are X miles away from a given library, you should be able to browse its collections from your mobile, potentially checking out a piece of information that the library has in its archives and holding onto it, moving on to another localized collection as you walk around a city.

This new world will be a radical shift for libraries. Library buildings won’t go away; we will still have a lot of materials that are worth caring for. Buildings will move more fully into their current dual nature, that of warehouse and gathering place, while our services and our content will live in the cloud, away from any physical place. The idea that one must go to a physical place in order to get services will slowly erode. The information that we seek to share and the services that we seek to provide will have to be fluid enough to be available in many forms.

Embrace the revolution

How do we prepare for this new mobile world? The three most important things libraries can do to prepare for the mobile shift of the next ten years:

Realize that the move to digital text and delivery isn’t going to go away. Embrace it. Be ready to digitize your unique collections, and ensure that they are available by every method and mode you can find. Hire librarians who are fluent in social networking, train those who aren’t, and provide funding for continuing travel and education. The language of the new web is related to the upcoming mobile revolution in significant ways. Be willing to decouple your procedures from your infrastructure, and don’t let the latter drive the former. Be willing to use the tools your patrons use, and don’t expect them to use the tools you want them to use.

The mobile technology revolution will change more than just our habits and the way we interact with information. It will change us at a deeper level and allow for interactions undreamed of in our current situation. Think about the ways that the most basic function of mobile devices, that of instantly available communication, has changed our lives in the last ten years. We no longer have to plan to meet someone-we can arrange for meetings on the fly. We no longer have to wonder where someone is-we can text them and find out. This level of communication was literally impossible just 25 years ago, and the next ten will make the previous 25 look like slow motion. We will move through a world of information, generating and consuming it with our every movement and action. Libraries must be poised to dip into this river of data and add their own information into the flow. This may happen invisibly, so that the patron may not even be aware of it. Librarians will have to add value to the everyday experiences of the student, the researcher, and the community member. The services attached to these new mobile devices are going to be the driving organizational and entertainment force for the next generation. If libraries can’t find a way to navigate these information rapids, we may find ourselves overturned.