Warning: This is a very long post. There are lots of resources mentioned, laws referenced, and opinions given. If you’re looking for a TL;DR version for a tweet, here you go:

Recent immigration enforcement efforts by the current administration should be alarming to libraries & we need to have action plans in hand.

Read on for lots, lots more.

Table of Contents

Libraries and Immigration

Threat Models

Why Libraries?

How to Prepare

Laws Regarding Resistance

Call to Action

Libraries and Immigration

With the release on Feb 21st of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) memos (one and two) detailing increased efforts relating to the efforts of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and related federal offices (Customs and Border Control ((CBP)) and the like), the threat that there may be immigration raids in libraries continues to grow. I have been trying to gather information about such threats since the initial increase in ICE raids began just a few weeks ago, and here is what I’ve discovered, links to resources, and some of my thoughts on the matter.

Since Trump took office, ICE and CBP have been on a much, much looser leash when it comes to the allowances they have to question, detain, and remove non-citizens from the US. Reports of mothers being removed from their children, removal of someone after a court appearance, arresting people leaving church-based hypothermia shelters, and the like have shown a willing disregard for humanitarian instincts and that no location should consider itself safe from the threat of immigration officers entering your space, questioning individuals, and potentially removing them for deportation.

Threat Models

As I see it, there are two threats for libraries that emerge from the current reimagining of US immigration policy. The first is similar to the threat that the PATRIOT act and other historical efforts have illustrated: the use of library-gathered information to target or identify an individual or group of people. That information could be circulation records, attendance lists for library programs, library card records, and the like. Libraries are aware of the threat to these sorts of records, there are State laws that outline limitations and protections for that information, and we have a history of protecting it. There are myriad resource that will give libraries tips on how to manage their technology in such a way to limit the information they keep, and action plans that outline how to react to an information request.

The second threat is, however, a new(ish) one. That threat is to the patrons inside or around your library, and the threat that an “enforcement action” could result in ICE agents entering your building, asking patrons for proof of citizenship, detaining those that cannot provide such, and expeditiously moving those patrons into “detention centers” and from there to deportation and out of the US entirely. If we protect patrons information so closely, with so much effort and vigor, how much more effort must we put forth in protecting the patrons themselves? What are the limits of protecting individuals in your community?

Why Libraries?

Given libraries’ efforts in assisting immigrant populations of the US, and that many libraries provide significant citizenship assistance, we should be very aware of the potential for a visit by ICE officers. Public libraries in particular should have an action plan for this, in the same sort of way that we had action plans for an FBI visit post-9/11 in regards to the PATRIOT act.

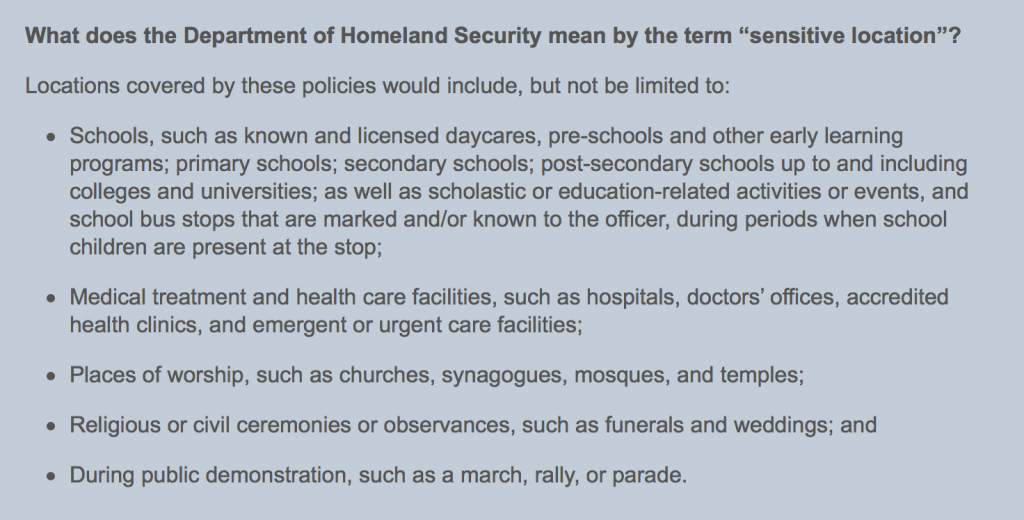

The Department of Homeland Security does specify “Sensitive Locations” within which ICE must meet a higher degree of legal proof before they are empowered to enter, question, detain, or remove someone. These include schools, hospitals, churches, and more:

it is worth noting that libraries are NOT called out in this list. It’s possible that they could be construed as part of “educational-related activities,” but in practice that refers to school activities that may take place after official school hours. I do not believe that any of the above categories affirmatively includes libraries.

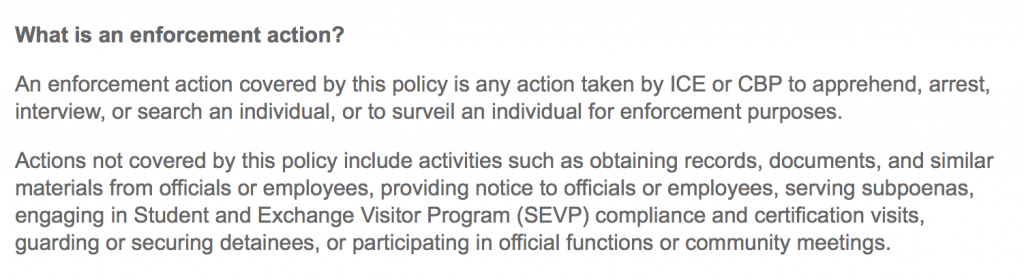

Even if libraries WERE to be construed as Sensitive Locations, that designation only protects what ICE refers to as an “enforcement action”:

The question of what powers ICE and CBP can bring to bear is a complicated one. Within the borders of the US, ICE has particular limits to their operations. They cannot enter a private home without permission or a warrant, for example. However, there is special legal dispensation given in US law to what is commonly known as the 100 Mile Zone, that is, any area within 100 miles of the border of the US.

As you may note, that 100 mile zone includes enormous sections of the population of the US, including the entirety of Florida, Hawaii, Maine, Michigan, and most of the largest cities (New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, Miami, San Francisco, and more. Within this zone, CBP has more authority to pursue immigration issues. The memos linked above direct ICE to hire an addition 10,000 agents, and CBP to hire an addition 5,000 agents, in order to pursue immigration issues more aggressively. I hope that it is obvious why this might be worrisome.

Finally, while we are seeking things to worry about, there’s the Delegation of Immigration Authority Section 287(g). This allows the Department of Homeland Security to “partner” with local and/or state law enforcement and thus allow the local officers to act on immigration issues…effectively, a form of ICE deputization. The memos linked above also direct ICE to more regularly use this in their enforcement efforts, increasing the number of officers available to detain and arrest immigrants even further.

How to Prepare

Given the combination of the broad powers assigned to DHS and the zeal with which the current administration appears to be going after immigrants, I believe strongly that it would be a dereliction of our duty to our communities to not consider how to respond to the potential of immigration officer activity in your library. This is a situation of not if, but when.

The resources linked below are almost all available in both English and Spanish, and most of those that are designed to be handed out to patrons are available in several languages.

A first step is being the information resource that your patrons need. Print and distribute rights cards for your patrons, so that they understand what their rights are here in the US, and how they should and shouldn’t interact with ICE agents. Here is a page with even more resources for patrons, many of which you could provide in your buildings.

This Community Raid Preparedness Checklist is a fantastic resource (with more coming from the same group), and outlines several steps that libraries should be looking at as quickly as they possibly can. NILC also has a presentation called Raids: What is Happening and How to Respond that was put together jointly with the Southern Poverty Law Center, and other stakeholders just a week ago that outlines the current state of things as well as possible responses.

The National Immigration Project has a variety of other amazing resources that libraries should have on hand, discuss, and implement where they can, including this FAQ that answers questions in a framework that I feel is very useful for libraries.

Finally, the most thorough response document I have found is this one, the Defend Against ICE Raids and Community Arrests toolkit, which has well-considered suggestions, resources, and ideas in it. It focuses on home raids, but much of the advice can be adjusted and used for public places.

ALA has a Libraries Respond page entitled Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers with links to ALA statements on service to these communities, as well as a few external links to resources. Some of the resources are older than I would like, but there are links to more current news reporting on the current situation. I would prefer to see ALA taking a much stronger stance on this, but understand their limitations.

Laws Regarding Resistance

In classic Internet style, here is where I remind you that I Am Not A Lawyer. Luckily, my friend Kyle K. Courtney is a lawyer, and a damned good one. He is, however, not your lawyer, and this section is meant as a summary of possibly applicable laws and cases regarding interfering with federal officers. The more you know, the better off you are in developing your action plan. Take it away, Kyle:

The concept of resisting, opposing, impeding, intimidating, or interfering with federal agents’ duties has been considered by the courts for decades, and is governed by federal statutes. It is important that you know and understand the law surrounding these actions. While we outline some of the major laws here, there are usually a large segment of ways you can be held or, of course, simply detained and later charged with misdemeanors.

Main Federal Statutes

18 U.S.C.A. § 111

This federal statute makes it a crime for anyone forcibly to assault, resist, oppose, impede, intimidate, or interfere with certain enumerated federal officers and employees while they are engaged in the performance of their official duties.

Note also that 18 U.S.C.A. § 1114 is critical to determining the official status of the person assaulted, so, in order to fall within the scope of 18 U.S.C.A. § 111, the person assaulted must be within the definition of government officers, etc. as defined in § 1114.

The statute provides for two offense levels:

- simple assault—a misdemeanor

- forcible assault—a felony

- Enhanced penalty for a forcible assault that involves use of a deadly or dangerous weapon or one that inflicts bodily injury.

The elements of the offense of an assault on a federal officer are:

(1) a forceful assault;

(2) committed voluntarily and intentionally;

(3) against an officer employed by the federal government who was then engaged in the performance of an official duty or on account of the performance of official duty.

*Cases have found that § 111 does not require that the assailant be aware that the victim is a federal officer.

- The scope of what a federal officer is “employed to do,” for purposes of determining whether an officer is engaged in the performance of official duties within the meaning of the statute, is not defined by whether the officer is abiding by the laws and regulations in effect at the time of the incident, nor is the touchstone whether the officer is performing the functions covered by his or her job description. Rather, the test is whether the officer was engaged in what he or she was employed to do rather than being on what the courts refer to as a “personal frolic.” There is no bright-line test, it is a case-by-case factual judgment.

28 U.S.C.A. § 1501

There is also a lesser offense of willful and knowing obstruction defined in 28 U.S.C.A. § 1501, making it a misdemeanor to obstruct, resist, or oppose any officer of the United States in attempting to serve or execute any legal or judicial writ or process.

A § 1501 violation contains all of the elements of a § 111 violation, except the element of force is required for a conviction under § 111.

18 U.S.C.A. § 1071

§1071 makes it a federal offense for a person to harbor or conceal any person for whose arrest a warrant or process has been issued under the provisions of any law of the United States, so as to prevent that person’s discovery or arrest, after notice or knowledge that a warrant or process has been issued for his arrest.

The federal offense of harboring or concealing a fugitive so as to prevent his discovery and arrest may be viewed as being comprised of three elements. Thus, in order for § 1071 to be applicable there must be:

(1) an act or acts of harboring or concealing done so as to prevent the discovery and arrest of an individual;

(2) a warrant or process issued under the provisions of any law of the United States for the arrest of the individual who is harbored or concealed; and

(3) notice or knowledge on the part of the person who performs the act or acts of harboring or concealing, before the performance of such act or acts, that a warrant or process has been issued under the provisions of any law of the United States for the arrest of the individual who is harbored or concealed

Sample Cases

The following caselaw is a sample of the enforcement of the federal statutes listed above. Some are specific to immigration and border patrol officers, while other are interpretations of the statutes for any enumerated federal officers and employees. There are even a few cases where third parties attempt to resist, oppose, impede, intimidate, or interfere with federal officers that are engaged in the performance of their official duties, namely arresting another party.

| CASE CITATION | SUMMARY |

| Bennett v. U.S., 285 F.2d 567 (5th Cir. 1960) | In a prosecution for assault on an immigration officer, it is not necessary to prove scienter, that is, that the accused knew the object of the assault was a federal officer (Border Patrol officers in plain clothes on horseback) |

| U.S. v. Varkonyi, 645 F.2d 453 (5th Cir. 1981).

|

It is no defense that the accused was attempting to protect his or her private property from trespassers who were immigration officers. |

| United States v. Vigil, 431 F.2d 1037 (10th Cir. 1970)

|

Third person does not have right to assist in resisting the arrest of another if third person knows or has good reason to believe the person making arrest is government official authorized to make arrest and official is not clearly using unnecessary force. |

| United States v. Ulan, 421 F.2d 787 (2d Cir. 1970)

|

Demonstrating bystander, who voluntarily intervened and struck federal deputy marshal in attempt to prevent arrest of co-demonstrator was found guilty of assaulting and interfering with federal deputy marshal in performance of his official duties |

| U.S. v. Davis, 690 F.3d 127 (2nd Cir. 2012) | Evidence was insufficient to support defendant’s conviction for misdemeanor of resisting arrest which showed only that defendant ran from a DEA agent and, when tackled to the ground, struggled against being handcuffed, primarily by putting their hands under their stomach. There was no evidence that defendant engaged in any conduct that demonstrated a desire to injure an agent or would cause an agent to apprehend immediate injury. |

| U.S. v. Steele, 550 F.3d 693 (8th Cir. 2008) | When defendant’s mother gave federal officer permission to enter her house and defendant was extremely angry and made threatening gestures, a reasonable juror could determine that defendant was not justified in using force to resist arrest. |

| U.S. v. Span, 970 F.2d 573 (9th Circ. 1992) | Defendants do not have a right to resist arrest by federal officers even if supported by probable cause |

| U.S. v. Cunningham, 509 F.2d 961 (D.C. 1975) | Federal officers engaged in performance of their duty may not be forcibly resisted; the subject of officers’ action must submit peaceably and seek legal redress thereafter. |

| U.S. v. Beyer, 426 F.2d 773 (2nd Cir. 1970) | Even if warrant of arrest or arrest itself had been invalid, defendant was not entitled to resist arrest by physically assaulting federal officer executing warrant |

| Darrah v. City of Oak Park, 255 F.3d 301 (6th Cir. 2001)

|

Federal court (applying state law) found that while arrestees have the right to use physical force to resist an unlawful arrest, third-party intervenors do not have the same right. |

| United States v. Heliczer, 373 F.2d 241 (2d Cir. 1967)

|

Bystander was guilty of assaulting a federal narcotics agent and interfering with agent’s performance of official duties because bystander attempted to kick one of the agents, even though bystander had opportunity to inquire of the agents about the arrest of another party, but did not do so.

“[A]s a general rule, he has no right to intervene if in fact a lawful arrest is being made by a federal agent, whether the bystander knows it or not, because, like the person being arrested, he is subject to [other caselaw] and to a great degree takes a chance in assisting another to resist arrest.” |

| Amaya v. U.S., 247 F.2d 947 (9th Cir. 1957) | Defendants, suspected to be aliens by an immigration officer, were found guilty of who 18 U.S.C.A. § 111, when immigration officer entered a public café and commenced asking persons therein suspected to be aliens as to their place of birth. The officer was struck by the first defendant while questioning the man, who was edging toward the front door. As the officer attempted to handcuff the first defendant, a co-defendant jumped the officer and took his gun. |

| U.S. v. Cho Po Sun, 409 F.2d 489 (2d Cir. 1969) | Two immigration officers, employed to assist in obtaining compliance with immigration laws, were assaulted by the defendant when they went into the kitchen of a restaurant where six Asian employees were present and asked the defendant questions as to his citizenship status.

*Note: The court rejected the defendant’s argument that the officers had no right to interrogate him, since he was neither an alien nor a person reasonably believed to be an alien whom they were authorized by 8 U.S.C.A. § 1357 to interrogate. |

| United States v. Cain, 413 F. Supp. 2d 197 (W.D.N.Y. 2006)

|

U.S. Marshals were arguably engaged in the performance of official duties when they were allegedly assaulted while assisting state officers in executing a state arrest warrant, acting pursuant to a MOU where state and federal officers worked together in apprehending persons with outstanding state and federal bench warrants. |

Call to Action

I feel strongly that the aggressive pursuit and removal of immigrants, in the manner of the current administration, is morally wrong and inhumane. It is driven by racism and xenophobia, and has at its base some of the ugliest of human beliefs. In Stand, Fight, Resist I wrote:

Libraries are powerful forces for good. Now is the time to muster our powers, to stand brave against the people who seek to limit and reduce our rights and our understanding of the world….This country, and the people in it, deserve a better world than the one that is currently being forced upon them. Use your power as pillars of your communities, as the guardians of knowledge and the providers of help, use that power now to resist the normalization of fascism and bigotry, of hate and fear and greed. Stand for truth and knowledge, justice and equity for all. Stand for facts, and stand for those who are most at risk. Stand against the horrorshow revealing itself to us, and fight with those who are determined to create equity among people, justice in the face of the unjust, and love out of hate.

I’m not sure how to say it better than that. Libraries must stand for justice and freedom for all people, for the best parts of our republic. We need to continue to fight on the information front, to show that immigrants who come to this country bring with them the strength that will make the US better than it is now.

Concretely, libraries need a clear and direct set of policies that outline their response to an immigration enforcement action. We need to have those in place now, as quickly as possible. There needs to be a clear set of directives for your staff, meetings to gather feedback and to clarify your local threat model (libraries on borders will have very different sets of threats than non-border libraries), and connections made with local civic and non-profit groups that are already active in this space. You need to have meetings with your Mayor, City Council, and local representatives about this issue. We need to be ready to protect our communities.

As bad as things are in this moment, they are going to get much, much worse. The administration has a stated goal of the removal of all undocumented immigrants in the US, which amounts to over 10 million people. There is no way to do this humanely, or with respect for human dignity and agency. It is the equivalent of rounding up, processing, and deporting every single person in New York City and Chicago, combined. It is easy on the Internet to fall into Godwin’s Law, and until recently one could expect that comparison of a current practice to the Nazi Party was, in fact, somewhat hyperbolic. Rounding up 11 million people, placing them into “detention centers” and attempting to remove them from our society…I’m not sure there are comparisons other than the Nazis that make any sense of it.

We are better when we embrace differences, when the marketplace of ideas is a bustling mercado and souq. None of us is as smart as all of us, and we are going to need all of us if we are to find that future where the United States is still a shining city upon the hill. That light is dimmed now, and sputtering, but it isn’t dark just yet. Libraries are partial keepers of this flame, and we need to be prepared to protect the people in our communities when they are threatened, however and whenever we can.