This year I have a small number of international speaking engagements, and I just returned from the first of those in 2017…which means it was the first since the recent spat of increased DHS and Customs enforcement. It was also my first trip to a Muslim-majority country, and while not one on the magic list, it still made me consider my re-entry into the US and the possible attention therein. These things combined to make me far more attentive to and aware of my personal information security (infosec) than every before. This post will be an attempt to catalog the choices I made and the process I used, as well as details of what actual technological precautions I took prior to leaving and when actively crossing the border.

This trip was to the SLA Arabian Gulf Library Conference, held this year in Manama, Bahrain, where I was on a panel discussing future tech. This means flying internationally through a major city, which for me meant flights from Nashville to JFK to Doha International Airport in Qatar, then finally to Manama, Bahrain. The return was was the same, with the exception of flying back into the US via O’Hare in Chicago rather than JFK. This meant crossing into at least 2 foreign countries physically on each leg of the trip, although in Qatar I remained in the international section of the airport and didn’t go through customs and enter the country proper. Still, there were LOTS of checkpoints, which meant lots of potential checks of my luggage and technology.

Threat Model

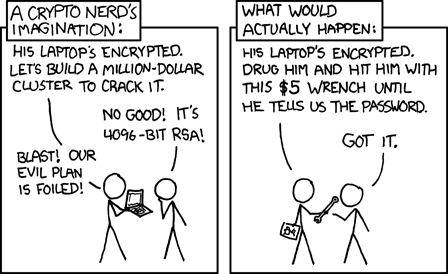

What was my concern, and why was I thinking so hard about this prior to the trip? After all, I’m a law-abiding US citizen, and as the saying goes, if you’ve nothing to hide, why worry? First off, the “if you’ve nothing to hide” argument is dismissible, especially given the last 6 weeks of evidence of harassment and aggression at the US border. I am a citizen of the US, but I have also been very outspoken online regarding my feelings for the actions of the current administration. On top of that, information security isn’t just about the individual…it’s about everyone I’ve exchanged email with, texted, messaged on Facebook, sent a Twitter DM, and the like….the total extent of my communications and connections could, if dumped to DHS computers, theoretically harm someone that isn’t me, and that was not ok in my book. A primary goal was to prevent any data about my communications or contacts from being obtained by DHS.

DHS and Border Control has very, very broad powers when it comes to searching electronic devices at the border. I was not certain of the power granted to Border Agents in Qatar and Bahrain, but my working assumption was they had at least the powers that the US Agents did. I also assumed that the US agents would probably have better technological tools for intrusion, so if I could protect my data against that threat, I was safe for the other locations as well.

A secondary goal in my particular model was to attempt to limit the possibility for delay in my travels. If I could comply with requests up to a certain point without breaking my primary goal of data protection, that would likely result in less delay. When considering these levels of access, I thought about questions like: could I power on my devices without any data leakage? Could I unlock my devices if requested and allow the Agent to handle my phone, for instance, without risking data leakage? Could I answer questions about my device and the apps on it (or other apps in question, for instance social media accounts such as Facebook or Twitter) honestly without risking data leakage?

With all of that in mind, here’s how I secured my technology for border crossing. Your mileage may vary, as your threat model may be very different, and the manner in which you choose to answer the various questions above may be different. If everything had gone south and my devices were impounded, I’d be writing a very different post (and contacting the EFF). But for this particular trip, this is my story.

What to Take

First off, I decided quickly that I wasn’t going to travel with my MacBook Pro. I was lucky enough that I didn’t need it for this trip, because there wasn’t any work that I would be doing on the road that necessitated a general purpose computer. I had work to do, but it all involved writing…some email, some writing text for a project, some viewing of spreadsheets and analysis of them. Simple and straightforward things that luckily could easily be done with a tablet and a decent keyboard. I already had an iPad with the Apple keyboard case, which made for an easily-carried and totally capable computing device for the trip. I could load some movies and music on it, fire up a text editor, answer email, and generally communicate without issue. It’s also iOS based, which makes it enormously more secure than Mac OS from first principles.

Since both my main computing device and my phone ran the same OS, I was able to also double-up any planning and efforts in security, as any decision I made could be equally applied to both devices. This turned out to be very, very convenient, and saved me time and effort.

The first thing that I did was backup the both the iPad and iPhone to a local computer here at my house (not iCloud) and ensure that those backups were successful. I stored those backups on my home network to ensure their safety…if anything went wrong later, these would be my “clean” images that I could revert to upon returning home. Then I used Apple Configurator 2 to “pair lock” my devices to my laptop, which would remain at home.

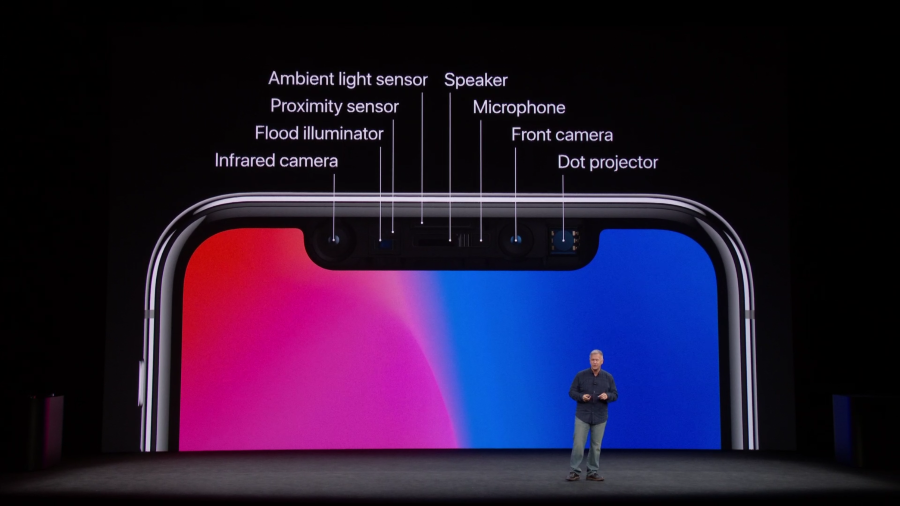

Pair Locking

This process was best described back in 2014 by security researcher Jonathan Zdziarski. While his instructions are fairly out of date, the general idea is still there and still works in iOS 10 and Apple Configurator 2. Basically, pair-locking an iOS device is a method by which the device is flashed with a cryptographic security certificate that prevents it from allowing a connection to any computer that doesn’t have the other half of the cryptographic pair on it. This means that once locked to my laptop (which, again, wasn’t in my possession and was still at my home), my iPhone and iPad would simply refuse to connect to any other computer in the world…whether that was someone that stole it from me and and attempted to reflash it using iTunes on their computer, or whether that is a diagnostic device being used by law enforcement.

This process is designed with the concept of using it for enterprise installation of iOS devices that need high security procedures to prevent employees from being able to connect their home computer to their work phone and retrieve any information. But it works very well for the purposes of preventing any possible attacker from accessing the phone’s memory directly through it’s lightning port. This processes ensures that even if the phone is unlocked and taken from my possession, DHS or other attacker cannot dump the memory directly or examine it using typical forensic information gathering devices.

Password Manager

Once both devices were pair-locked, I was left with two freshly installed iOS devices that I needed to reload with apps and content that would be useful for me. After loading a set of games and apps that would allow me to pass the time and still get some work done, as well as media I might want to consume on the road, I loaded my password manager (I use and am very happy with 1Password) and created a very, very long and complicated vault password that there was no possibility I could remember. I recorded that password on paper (left at home in a fireproof safe) and gave it to a trusted person that had instructions not to give the password to me until I had cleared the border and only over a secured channel.

I then changed the 1Password vault password to be that password plus a phrase that I knew and could remember (a sort of salt). 1Password was set up to allow me to login with TouchID, so I could still operate normally (logging into services and such) until such a time as that TouchID credential was revoked. Once revoked, I would be completely locked out of my passwords, with no ability to access them, until through a pre-arranged time and secure channel I got the vault password from either of the mentioned trusted sources. Those trusted sources, meanwhile, couldn’t access my password vault either, since the salt was resident only in my head.

It may be obvious, but I also ensured that everything in my life that was accessed with a password had a very strong one that was held by 1Password, and that I didn’t know and couldn’t memorize even if I tried. My bank, social media, dropbox…everything that could get a password, had a very, very secure one. Any service that supported 2-factor authentication had said 2 factor turned on, with the second factor set to an authentication app that supports a PIN (or, in the case of Very Important Accounts, a physical Yubikey that was left in TN as well). This is security 101, and not directly related to my border crossing…but if you don’t have the basics covered, nothing else really matters.

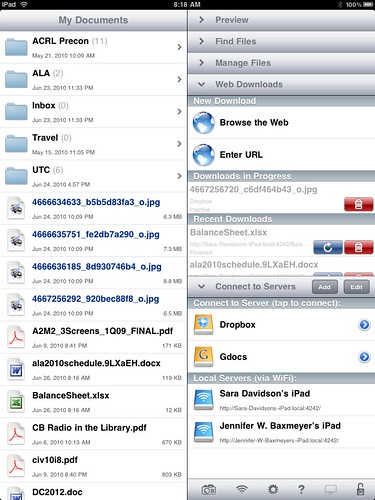

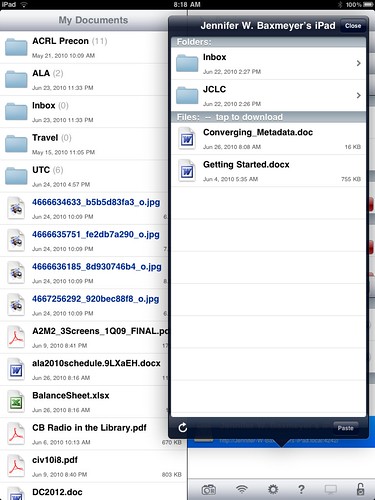

Sanitization

I made sure that iOS had most iCloud sync services off….no contact syncing, no calendar syncing, really the only thing I left syncing was my photo gallery. I did not install any social media apps (no Facebook app, no Twitter app, etc) and only logged in and out on the websites in question. The browser on both devices was set to not remember passwords, and I clear cache and history regularly when traveling. As far as I could, I eliminated anything that stored conversations or messages between myself and others…no Facebook Messenger app, etc. I deleted my email app, and didn’t enter my account information for email into the standard iOS mail app.

This was, keep in mind, just for the transit period. Once in country and across borders, I could use a VPN to connect to the ‘net and download any apps needed, log into them after retrieving the password from one of the trusted sources, and effectively use both devices normally (with basic security measures in place all the time, of course).

Crossing Borders

At this point, I had a device that couldn’t be memory dumped, that had very little personal information on it, and even less information about my contacts on it. It mostly acted normally for me, because 1Password handled all of my logins and I used TouchID during daily usage…right up until I needed to cross a border. Before I did so, I deleted my TouchID credentials via Settings (by deleting the fingerprint credential), and powered-cycled my phone. Those two actions did several things all at once:

The first was that it prevented me from being able to know or retrieve any passwords for anything in my life. That’s a pretty scary situation, but I knew it was fixable in the future (this wasn’t a permanent state). It also meant that if I were asked to unlock my phone, I could do so pretty much without anything of interest being capable of access. Without the ability to dump the phone forensically, officers could ask me for passwords for accounts and I could truthfully say that I had no way of telling them, because the password manager knew them all and I didn’t. And I couldn’t give them the password vault login because I literally didn’t know it.

The idea with all of this was to create a boundary of information access beyond which, if DHS wanted to try and access, they would need to impound the phone and potentially subpoena the information from me with a warrant. My guess (which turned out to be correct) was that they would ask to have it powered on, and maybe they would ask to see it unlocked, but that would be it. If they pried further, well…I was prepared to tell them truthfully that I didn’t know, that I couldn’t know. And I would call a lawyer if detained, and proceed from there.

The worst case scenario for me was minimal delay and discomfort. I am enormously privileged in my position to be able to think about this sort of passive resistance without actual fear for bodily harm or other forms of retribution. For me, the likely worst case, even if things had escalated to asking for social media passwords, would have been the confiscation of my devices and my being detained for a time. This is assuredly not the worst case for many, and it is extraordinarily important that each person judge their own risks when deciding on security practices.

For some, it is far better to simply not carry anything. Or to carry a completely blank device. Or purchase an inexpensive device when you arrive in the country of your destination. For me, I had the ability to prepare and be ready for resistance if needed. Your mileage may, and should, vary.

Conclusion

The results of all this thought and effort? Nothing at all. Not a single bit of attention was paid to me at the various border crossings, by either US or foreign agents. On the leg of my flight leaving Qatar, I went through no fewer than 4 security checkpoints from the time I landed until getting onto the plane taking me to O’Hare, and at each one there was a baggage scanner and metal detector, agents pulling people out of line for additional screening, and the like. When I finally got to my gate, it had its own private security apparatus, again with metal detector and baggage X-ray. At this security checkpoint, I was randomly selected for additional screening, but the agent in question (a Qatar security agent) was incredibly professional, thorough, and neither invasive nor abusive. I got a pat down (much less severe than those I’ve been given at US airports), and they asked to look inside my carryon…they even asked me to power on my iPhone and iPad. But they didn’t ask to unlock them, and they didn’t ask for passwords of any type.

When entering into the US at O’Hare, the plane was greeted by DHS agents at the gate, who asked to check passports upon exiting the plane. The agent I was greeted by barely had time to glance at my US Passport before waving me through…again, the privilege of my appearance and nationality was evidenced by the fact that several of my fellow passengers were not waved through so easily. The last thing I heard as I walked up the jetway towards Customs was a DHS Agent saying to the robed gentleman behind me “So you don’t speak very much English, huh….”

The current state of our country cannot stand. We are a nation of immigrants many peoples1, and a nation that believes in the privacy of our affairs and effects. This concern I had for my own and my friends’ information shouldn’t have been necessary. We should be able to be secure in our possessions, even and especially when those possessions are information about ourselves and our relationships to others. I do not want to be in a position where I have to threat model crossing the border of my own country. And yet, here we are.

I’d love any thoughts about the process described above, especially from security types or lawyers. Any holes or issues, any thoughts about what was useless, anything at all would be great to hear. I hope, as I so often hope these days, that all of this information never becomes applicable to you and that you never need to use it. But if you do, I hope this helped in some way.

1 I was called out on Twitter for my use of “immigrant” as an inclusive term for people in the US, when, of course, many US citizens ancestry is far more complicated and difficult than “they chose to come here”. It was written in haste and while it works for the emotion I was attempting to convey, it definitely undercuts the violent and difficult history of many people in the US. I’ve edited the text to reflect the meaning more clearly and left the original to indicate my change.